Grammar

U2D uses a system similar to UNLWS, simplified in some regards and complexified in others. Instead of 1 kind of glyph, there are 3: nouns (usual UNLWS predicates), verbs (indicated by circle) and relations (line decorations like UNLWS, but syntactically different from nouns in U2D). Meanwhile, it lacks a good deal of the syntactic sugar UNLWS has, such as scalar families.

This page is a complete guide to the grammar of U2D. It is organised with the specifics of the grammar, such as nouns and verbs, at the top, and the higher-level concepts, such as layout and reading large texts, at the bottom.

ToC

Basics

U2D is a 2D writing system, where meaning is expressed via glyphs and their relations in a nonlinear way. There is no direct spoken component to a 2D writing system, because there are no clauses or sentences; a piece of writing is holistic and in general indivisible.

The scale and orientation of components does not explicitly affect the meaning of a piece of writing, but may do implicitly: distance may indicate spatial, temporal or conceptual spacing; orientation also may indicate certain relations. Nonetheless these are optional and uncodified. Nouns are unchanged under reflection, but verbs and relations are not.

Nouns

A noun is a glyph that expresses a concept. There are on the order of 100 simple glyphs, glyphs that cannot be visually divided. They are categorised by shape and stroke count; more on this at the glyph page. Complex glyphs may be made up by joining simple glyphs along faces.

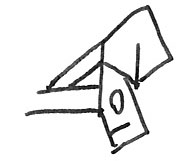

These joinings may be in any order and orientation; simple glyphs can be reflected and rotated as you wish, preferably according to aesthetics. The scale, however, is fixed within a complex glyph: faces must match. All of these mean the same thing:

Usually, the meaning of the complex glyph is predictable from its components. For example, above: Island + Woman = Islander (female). But this is not guaranteed; the complex glyph is an entity unto itself, and its makeup is not grammatical. For example,

Yes + Butterfly = Beautiful. Who would have thought? There are no strict rules here. (Of course, 'Beautiful' here is a noun, so perhaps more literally it's "Beautiful Thing". This is how simple adjectives tend to work in U2D.)

Binding nouns

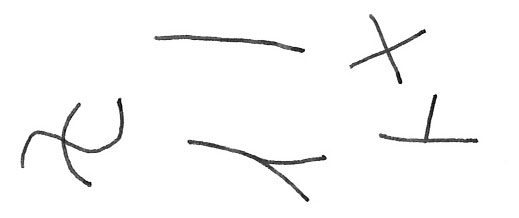

All meaning in U2D is constructed, one way or another, by connecting glyphs together. Connections are lines drawn between glyphs; they can join, divide, go anywhich way as long as it's clear they're still lines:

The simplest kind of connection is just a plain line, and expresses equivalence, equality, "is".

The above means "The islander is beautiful". Or, it might as well say "An islander is beautiful", or "The islanders are beautiful", or perhaps "Islanders in general are beautiful" (see the definiteness and number section below). And that's a rather short and uninteresting connection; we could just as well write

and it would mean the same thing. Connections are called bindings, as per UNLWS, for no particular reason; you would say that Islander is bound to Beautiful in the example above.

Note that lines cannot cross and retain separate meanings (like they can in UNLWS). If you connect lines, you are equivocating them, end of story.

Definiteness and number

As above, it's not clear whether our noun means "An islander", "the islander", plurals thereof, "islanders in general", etc. In grammatical terminology this is called 'definiteness': "an islander" is indefinite, "the islander" is definite, "islanders in general" is generic.

U2D by default is indefinite. Any noun is taken to mean a new instance of that noun (although not necessarily nonequivalent to another instance of that noun, but very likely so). Definiteness is not needed, because its function is to refer to a previously mentioned or otherwise understood referent (noun/thing), and if you want to do that in U2D you can bind to when you first wrote that noun. External specificity (I might say "The Queen", and you may know who I mean even though I haven't mentioned her before) is achieved implicitly; you can write "queen", or be more specific and write "queen of England".

Genericness is marked as a relation, and is explained further below.

Number (singular/plural) is not marked by default. This is not catastrophic; many spoken languages also do this. A noun by default is of indeterminate number, and it may be understood from context. The number may be marked explicitly, by writing the equivalent of "one tree", "two trees", "several trees", "many trees", etc. (see the section on numbers below).

Verbs

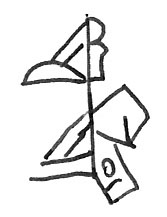

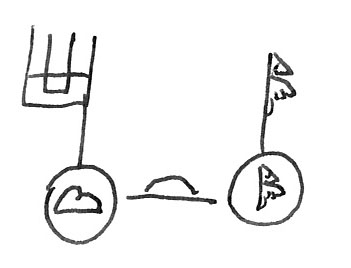

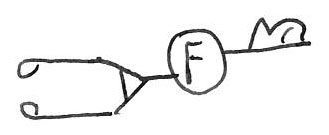

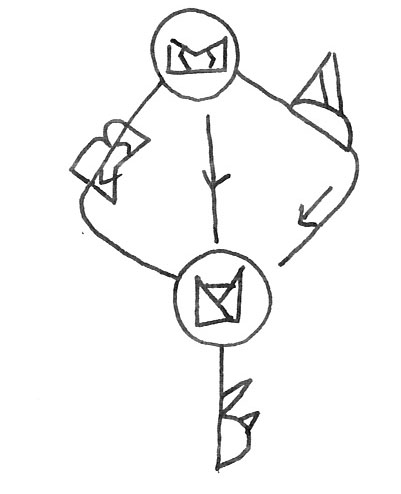

Verbs are indicated by a circle around a noun. Its arguments (subject and object) are bound to the outside of the circle. The bindings are counted clockwise from the bindings with the largest gap behind it (the 'first' one clockwise).

In the case of there being two bindings, the first binding is the object and the second is the subject.

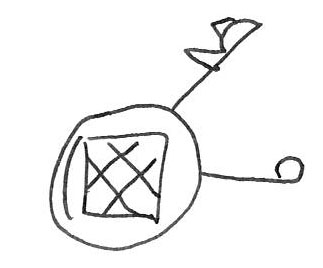

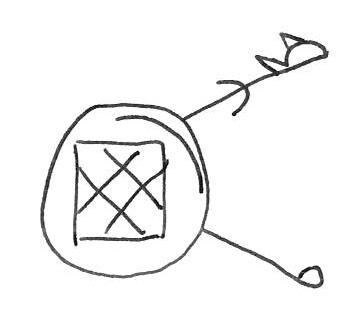

"A man catches a fish." Here, Net is inside a noun and means Catch. Fish is the object of the verb and Man is the subject.

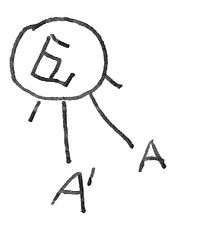

The rules for how these arguments are bound are a bit complicated. In the visual examples below, letters are used instead of nouns. 'A' is always the object and 'B' is always the subject.

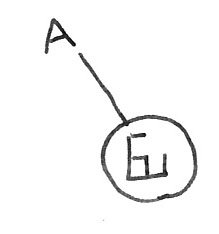

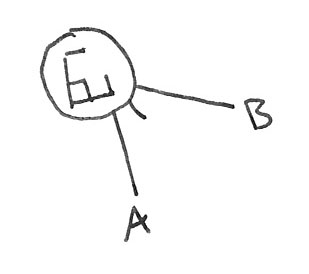

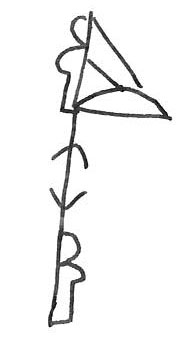

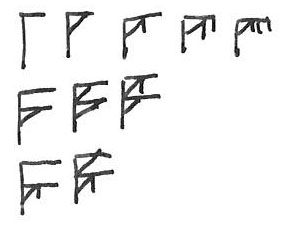

- For a single argument, this argument is the object by default. A is made:

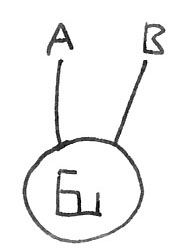

- For two arguments, the first is the object and the second is the subject. B makes A:

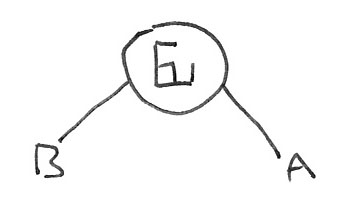

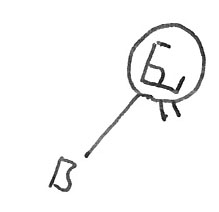

- These can be marked explicitly by the use of a small line to denote the 'start' of the arguments. B makes A:

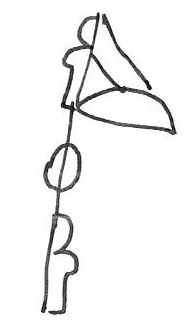

- A second small line denotes the start of the subjects. B makes (something):

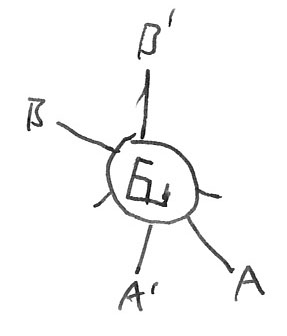

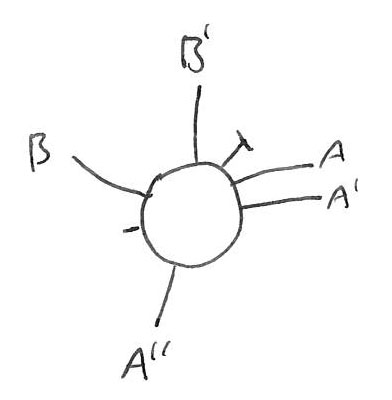

- Multiple subjects/objects must be made explicit by use of both of these markers. A and A' are made:

B and B' make A and A':

Be aware that the first marker is determined only by considering the two markers (arguments are ignored), and is the one at the start (clockwise) of the smaller segment made by the two. This is the same criterion as used to decide the first argument. If absolutely necessary, the first marker can be made explicit by adding a horizontal line to it:

Note that one verb circle is taken to mean a single action*, and thus in the second-to-last example above, A and A' are made as part of the same action.

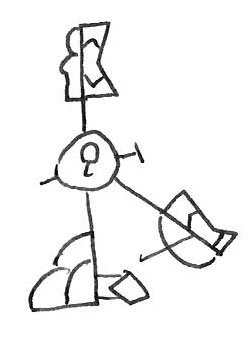

The action can be referred to directly by leaving a small gap between the binding line and the circle. Time, location, adverbs, causation, etc., are all expressed this way; you write "[the action] is [at some time / somewhere / something / causes... / etc.]".

"The man runs quickly", or, more literally, "The running of the man is fast". Here Wind is taken to mean Fast; in practice it is very obvious when a noun is being used in an adverbial sense, because it will be bound to a verb. Nonetheless this meaning is contextual.

An empty circle is also a verb; with one argument it is existence, and with more than one it is equivalence.

Subject and object may also be suggested by the orientation of the glyph inside the verb circle, which is otherwise without meaning. If the glyph has a clear direction (for example, the pupil in See pointing towards what is being seen), this may substitute for ordering of arguments around the circle.

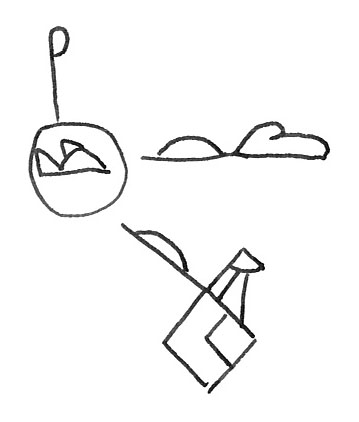

*Repeated, or habitual, actions are denoted by an arc (the 'habitual marker') inside the verb circle. It is then understood that the verb circle refers to a set of habitual actions:

If you were paying attention during the definiteness and number section, you may have noticed that this does not say, "I catch fish", or, more explicitly, "I tend to catch fish". It says, "I tend to catch a fish", that is, the same fish every time. Because we have constructed an instance of a fish, it is that fish that is the object in the habitual relation. Our writer must be throwing his catch back, and our fish must like being caught; and unless we bind a context such as "on one day", this seems to be happening every time the writer goes to fish. If we wanted to say "I tend to catch fish", and mean that we do, indeed, catch different fish sometimes, we would put a generic relation between Fish and Catch.

Relations

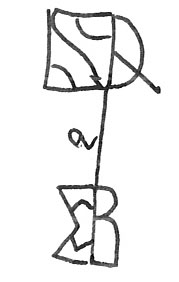

How would you write "A is at B"? 'At' could be a verb, but that's a bit tedious. A few of the most common relationships are abbreviated into line decorations and given the name 'relations'. The relation is placed 'above' the line it's modifying.

"The king has a fleet". Note that this is direction-specific; the side of the line that the relation is placed on becomes the top of the line, and the clause is then read left to right. For readability reasons, it's best to keep the relation in a set orientation.

Some relations are direction-specific, like ownership, and some are inspecific, like negation. Most are fairly self-explanatory, but one in particular is interesting: the context relation.

"I swim in the sea during the daytime." Here, the context relation functions as spatial and temporal; it's direction-specific here. And it can do more!

"Time moves like a bird". Here, Bird is the context in which Time Moves, metaphorical. More elegantly,

"Time flows like a bird flies." In this case, the context relation is direction-inspecific, and could be read either way. Nonetheless, Bird Flying is the context in which Time Flows.

Relations encompass a good deal of distinct semantic functions: negation, possibility, necessity, noun-modifying, verb arguments (other than subject and object), possession, genericness and comparisons. To name but a few. They can be chained to great effect.

Note that relations can be bound to like verbs. If you want to bind to an equivalence ('is') relation, you must use the equivalence glyph explicitly.

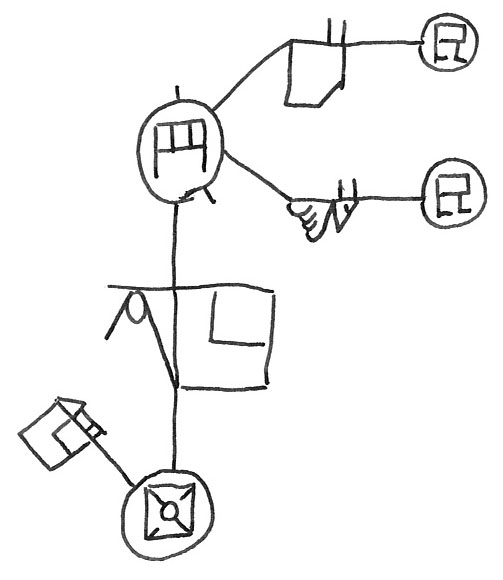

Relations can also be put inside verb circles and treated as verbs. This is recommended if you want to bind too many things to one relation, is necessary if you want to make a relation habitual, and is also useful if you have many similar relations close by:

What a chore to have all of those possession relations there. It would be nice if we could only have one; but beware. We cannot simply move the relation up past the branch:

Now "subject" and "royal boat" are bound together, meaning, rather nonsensically, that the queen's royal boat is a male subject of hers. This is a very easy mistake to make, even more so with causation. Correctly:

Possession is now a proper verb, and as such can have multiple objects (and subjects). But beware! The possession is a single action, so if we don't wish to imply that the queen's ownership of these things is somehow related, we mustn't write this.

Generics and specifics

What we call a 'generic' is an entire class of nouns; in English, "Men are pigs" has "men" as a generic here, because we are referring to all men, or, at least, a typical man. We are not constructing an instance of a man and saying that he is a pig; that would be a 'specific'. The generic relation 'converts' specifics into generics, and looks like this:

It is read, "[Left] is the whole class of [right]", or, equivalently, "[Right] is an instance of [left]". It is not that the left side is now a group of a lot of [right]s, but rather, it is the entire class of [right]s - a generic. This means that generics can only be directly bound to other generics (or instances that refer to classes). It is rather difficult to give an English example of such an absurdity (perhaps "Men are a pig", but, of course, we don't mean that some men got together inside a pig costume); suffice it to say that classes of nouns cannot be particular instances of nouns (unless such an instance is, itself, a class. Yes, you can have classes of classes. Yes, it goes all the way up). In fact, the possible uses for generics are rather limited. They can only bind to relations with other generics, or habitual verbs.

"I tend to catch fish". Both the habitual marker and the generic relation are necessary for this to really make sense. We could certainly not forgo the habitual marker, because then the writer would be catching the entire class of fish in one go. That would be some net.

As mentioned, generics can only be bound in equivalence to other generics. That means a construction with two generic relations facing each other is reasonably common:

"Female islanders are generally women." This may be abbreviated into a single relation, the general equivalence relation:

Pronouns

As a text gets larger, it becomes more difficult to keep the various bindings from getting tangled. If you've ever studied graph theory as an adult or tried the "Three utilities" problem as a child, you will know that in some situations you cannot prevent the lines from crossing.

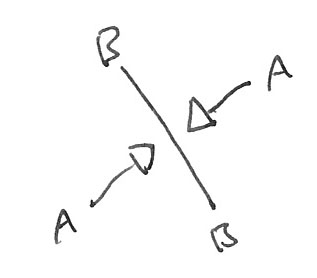

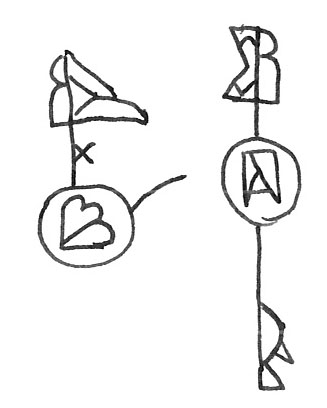

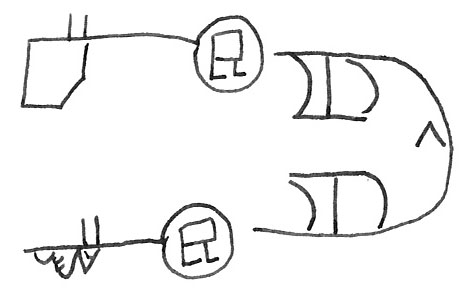

U2D's circular verbs and laxer noun bindings alleviate some of the difficulty, but things can still get out of hand very easily. U2D borrows UNLWS' pronoun system, whereby arrows are taken to remotely continue lines.

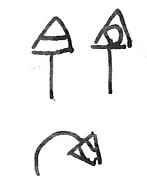

The two As are connected, as are the two Bs, but A is not equivalent to B. How convenient. Note that this is not the same arrow as the causation relation, or 'to'/'from'. As with UNLWS, the arrowhead may be filled with an arbitrary pattern to distinguish separate sets of pronouns.

These may be in effect at any range, although if a text is particularly large, it might be necessary to reuse pronouns once you're far enough away from other usages. Reading is helped greatly if the pronoun points towards another pronoun of the same kind. It is also suggested that you reserve the blank pronoun for very short-range bindings, like the one shown above.

"I" and "you" are also 'pronouns', in the more traditional sense. They behave roughly as you might expect; in the top-level, at least, "I" refers to the writer and "you" to the reader.

Joining

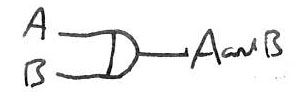

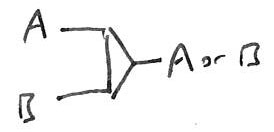

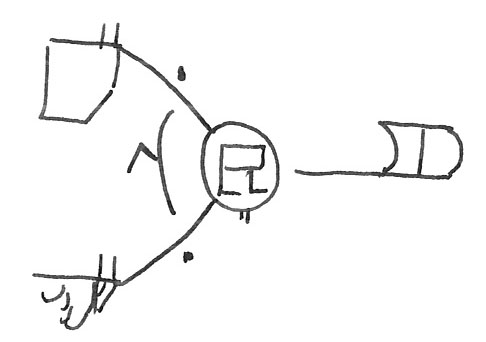

How might you say, "You and I pet a cat"? This is not a trick question; we can say this, if Me and You are both subjects to a verb Pet, with object Cat. But what about, "You or I"? There is no way to say this. Besides which, if we wanted to talk about Our adventures, would we have to bind both of us to each verb, and keep track of both of our lines separately? What if others joined our party; it would be quite illustrative, but awfully inconvenient, to have to draw ten separate lines if ten people are walking along a path. We want to be able to talk about groups of nouns as a single item. And into the bargain, perhaps we could specify a group of nouns that is "You or I". This is called 'joining', because we join lines together (albeit not in equivalence), and looks like this:

For clarity, the lines being joined (on the left here) must come in perpendicular to the face of the joiner, or the 'gate'. That said, the gate itself may look asymmetric:

And you may happily bind any number of lines to the face. "Or" in the case of more than two bindings will mean only one of those bindings.

"You or I pet a cat".

If your ears pricked up when you read 'gate', you may have recognised that the designs of these gates mimic logic gates; naturally, AND and OR gates. Together with the NOT gate, the negation relation, U2D is functionally complete, meaning that you can represent any Boolean operation, any logic gate, and any digital circuit... so long as your inputs are pure True and False (which may be realised as "Something is equivalent to itself" and "something is not equivalent to itself", respectively, among other options), and as long as they behave like they should when going through gates. Is a Truth and a Falsehood a Falsehood? It must be. And is a Truth or a Falsehood always a Truth? That seems nonsensical. But say no more.

Numbers

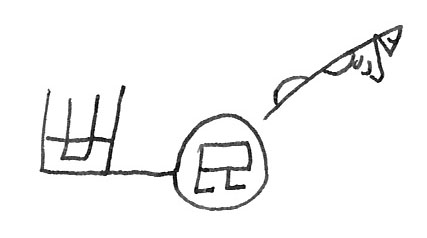

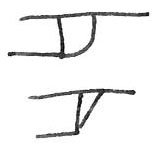

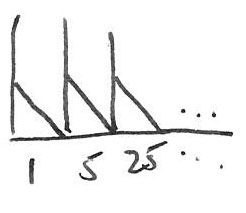

Counting in U2D is done in base 5. 0 to 4:

And 5 (105 - 10 in base 5):

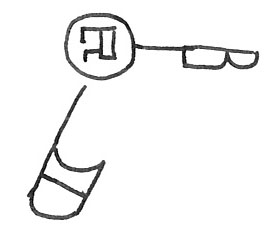

A number is a line with rows of markings along one side. Each row is a digit position (in base 5), and the furthest row from the binding is the least significant.

Hopefully it's obvious how this system extends to any positive integer. 0-7, 10 and 11 (05 - 125, 205 and 215):

31 (1115):

It is rather awkward, and difficult to read besides, to write a lot of 0 positions to represent large numbers. In effect, exponentiation is represented by putting another number on the back of the top row; this number is how many places have been skipped (and are presumed 0 or unknown). (2×1041)5, or 2×521, which is a bit under a quadrillion:

Higher exponents could perhaps be indicated by putting a number on the back of the first exponent, and so on. To be readable, these glyphs, like the numbers they represent, would have to be very big to be at all readable, since the size of the topmost exponent decreases exponentially as you go higher.

Cartouches

The cartouche is a dashed line enclosing a section of writing that is not being asserted by the writer. It's used for speech:

"The king says that he rules many islands", or, more literally, "The king says, 'I rule many islands'". Here, the cartouche is not closed; it is understood what is inside and what is not. The cartouche is bound to directly, to indicate that that particular idea is being spoken. "I" inside the cartouche refers to whoever is suggesting it: in this case, the speaker. "You" will refer to whoever it is directed towards (the listener, perhaps).

The cartouche is also used for certain conditionals:

"If a fisherman sees a fish, he catches it." Glyphs inside a cartouche can bind to things outside, or inside another one, as in this case. Cartouches can also bind to each other; cartouche A 'causing' cartouche B is understood to mean that if A were the case, B would be the case (because of A). Another kind of conditional that did not imply causation might link the two cartouches with a context relation (A is the case whenever B is the case).

It has many uses besides; if you write relations down outside of a cartouche, you are asserting them. So if you merely wish to consider a possibility, you will need to use a cartouche.

Relative clauses

Entire clauses, or larger sections, can also be bound to. This is indicated by distance:

What the islander does not like is bound further away than you might expect from the Take verb, so you read it as referring to the entire "King takes fish" clause. In more complex writing, the further away your relation is, the more you are binding to. If (and only if) absolutely necessary, the relative clause can be enclosed by a dotted boundary.

Complex phrases

Most of the grammar has been covered by this point, but you have yet to see anything that couldn't be expressed in a single English sentence. Of course, U2D glyphs can bind to as many other glyphs as need be, not limited to simple clauses.

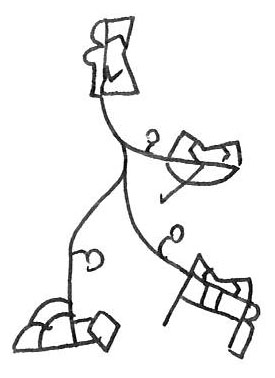

"The king rules an island. Because of this, he takes fish from that island." Hopefully it is clear what's going on here: King is the subject of both Rule and Take, Fish is the object of Take, Island is the object of Rule and what is being Taken From, and the Ruling is causing the Taking. This is still a fairly simple example; a piece of writing may expand to be a larger web of relations.

"A clock [time machine] tells [writes] the time [time now], and has a minute hand [bird hand] and an hour hand [rock hand], both of which move separately." What if we wanted to form a comparative? Say that the minute hand moves faster than the hour hand?

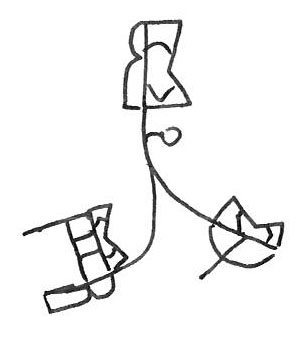

We could write this, but it's a bit tedious; we've written Move and Fast twice each. We could write, more idiomatically,

which could be rendered in English as "The hour hand moves quickly to a lesser extent than the minute hand." In this case we are comparing quantities of "subjectness", to what extent the nouns are subjects of the verb. Also note that we have broken our rule of "separate verbs for separate actions"; it is idiomatic, and in practice should be obvious.

Reading order

Since U2D writing can have any kind of topology, and is most definitely non-linear, there is no set reading order, or even starting position. The meaning of a text is the same regardless of what order you read it in. Nevertheless, in the case of narration, there is likely a path (or several) of maximum enjoyment for the reader. In the case of nonfiction this may be a path along which the writing is most clear, requires as little deviation as possible, etc.

Starting position, or multiple 'key' starting positions (around which noun constructions/definitions, important context, etc., may be closely located) may be indicated by particularly large nouns, prominence in layout, or anything else that's suitably obvious.

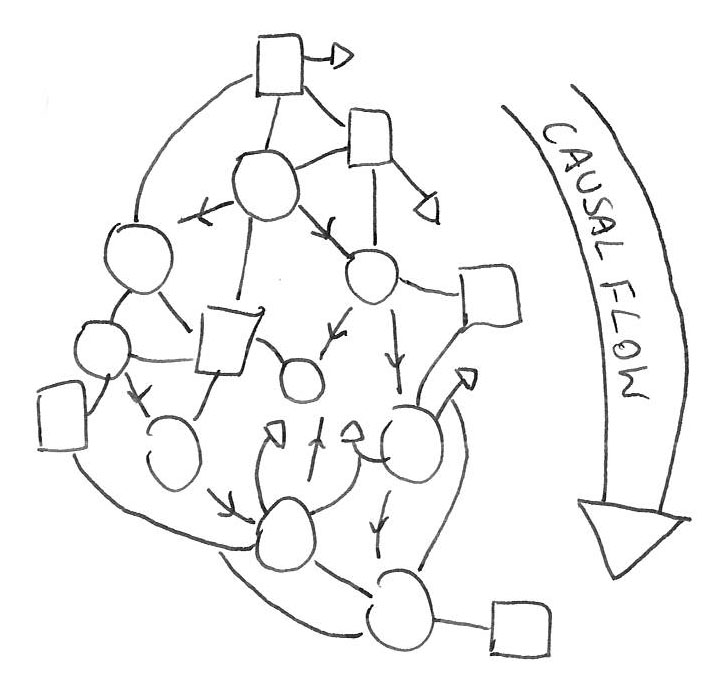

Reading order, if there is one, may follow a 'trunk' of relations, where divergences from this trunk are clearly marked, or soon rejoin. This may take the form of a tendency for causal relations to point in a particular direction, or anything else.

In the above illustration, nouns are abbreviated as squares and verbs as circles. Relations are not distinguished except for causal ones. The 'causal flow' down the page should be obvious from these relations.

Time

Verbs do not have tenses. Time may be indicated explicitly by context, as in "in the past", "in the present", "in the future", etc., but by and large will not be. Time is usually implicit given what else is being bound, e.g., if your story starts with "A long time ago...", verbs there will all have happened in the past.

What about time flow? How do we know what order things happened in? Causation is the most reliable indicator of this. If A causes B, A happened before B (as long as A and B are single events). The flow of causation relations will typically indicate the flow of time in writing, and as such, causation is marked much more commonly than might be in other languages. Even if two events are not particularly related causally, a loose causal link is enough to justify a cause relation.

Space on the page may also be used to indicate time. In the case of a causal flow in one direction (see above), it will be understood that clauses further along that relation happen later on, even if they are not bound explicitly. This may happen even without a clear causal flow, where one direction (or possibly distance from a point) indicates temporal distance.

Space and layout

Layout on the page may serve several purposes beyond merely grammatical. A writer is free to use layout on the page to their advantage. As above, it is very useful to express time ordering, but a direction on the page can also be physically spatial, or both, or anything you can imagine.

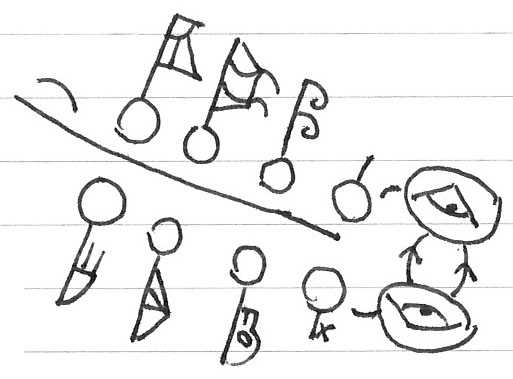

Layout can also be used to convey specific concepts. This is most clear in the Alan Watts example on the examples page. Towards the end of that text, some apparently agrammatical things happen:

Nothing here is wrong, it's just seemingly meaningless: relations connected to nothing. But some liberties were taken with the layout to imply a certain set of pairs: the 'light' things on one side of the central line and the 'dark' things on the other. The central line binds all of these existences to the context that has been cropped out on the left. And to the right, the lines are understood to refer to the whole stack of things on each side.

In English, this might read, "[In some context] there is light and dark, hot and cold, life and death, existence and nonexistence. Each of these is only perceived because of the other."

A final note: the last pair here, 'existence' and 'nonexistence' are not nouns. They are Exist verbs with an unbound object; literally, "Something exists" and "Something does not exist".